1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract, arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal within the myenteric plexus of the muscularis propria (Sanchez-Hidalgo, Duran-Martinez, Molero-Payan, et al. 2018). The stomach is the most common site of occurrence (56%), followed by the small bowel (32%), colorectum (6%), and esophagus (<1%) (Sanchez-Hidalgo, Duran-Martinez, Molero-Payan, et al. 2018). GIST has no known sex predilection and the median age at diagnosis is 60 with rare occurrences in children and young adults (El-Menyar, Mekkodathil, and Al-Thani 2017). The majority of cases are sporadic in nature, although GIST is occasionally associated with various genetic syndromes (Agarwal and Robson 2009). Most tumors show mutually exclusive oncogenic activating mutations for either KIT or PDGFRA, which determine their response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (El-Menyar, Mekkodathil, and Al-Thani 2017). GIST may exhibit a wide variety of symptoms depending on the location of the tumor, including small bowel obstruction, melena, hematemesis, weight loss, or early satiety; but it most commonly presents with gastrointestinal bleeding or without symptoms until it is externally palpable (Sanchez-Hidalgo, Duran-Martinez, Molero-Payan, et al. 2018). Metastasis, typically to the liver or peritoneum, is present at the time of diagnosis in approximately 50% of cases (Sanchez-Hidalgo, Duran-Martinez, Molero-Payan, et al. 2018). The recommended initial treatment for metastatic GIST is neoadjuvant therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor followed by cytoreductive surgery (Sanchez-Hidalgo, Duran-Martinez, Molero-Payan, et al. 2018).

The incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer, defined as a malignancy diagnosed during pregnancy or in the first year after delivery, has steadily increased within developed countries from 1:2000 deliveries in 1964 to 1:1000 in 2000, a change attributed to both a general increase in cancer incidence and to a propensity for delayed childbearing (Salani, Billingsley, and Crafton 2014). GIST represents an especially rare malignancy in pregnancy, with only 12 case reports appearing in the literature (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). Among these, the median age and median gestational age at diagnosis is 31 years old (range 21-42 years) and 18 weeks gestation (10-28 weeks), respectively (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). Two of these patients underwent pregnancy termination at seven and at 15 weeks gestation while on imatinib, while seven gave birth to healthy newborns, including two sets of twins (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). Only one of these cases was diagnosed in the postpartum period (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). There are no reported cases of metastatic involvement of either the placenta or the fetus (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). We present the case of a recurrent metastatic GIST diagnosed in the postpartum period following unexplained malnourishment, weight loss, and tachycardia in the late third trimester.

2. Case

A 31-year-old gravida 1 para 0 female presented for initiation of prenatal care at 34 weeks gestation due to recent immigration from Rwanda. She reported a history of a small bowel resection for a tumor with adjuvant imatinib therapy for one year. Because her prior medical care occurred internationally, her medical records were not obtainable. She was noted to have a superficial abdominal mass on physical exam. An abdominal ultrasound was performed and read as showing a sub-serosal fibroid measuring 7.3 x 4.7 x 4.5 cm and an anterior intramural fibroid measuring 4.0 x 2.8 x 2.1 cm. The patient reported decreased appetite throughout her third trimester with a 3 kg weight loss and was consistently tachycardic at each prenatal visit. An electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, and thyroid studies were within normal limits.

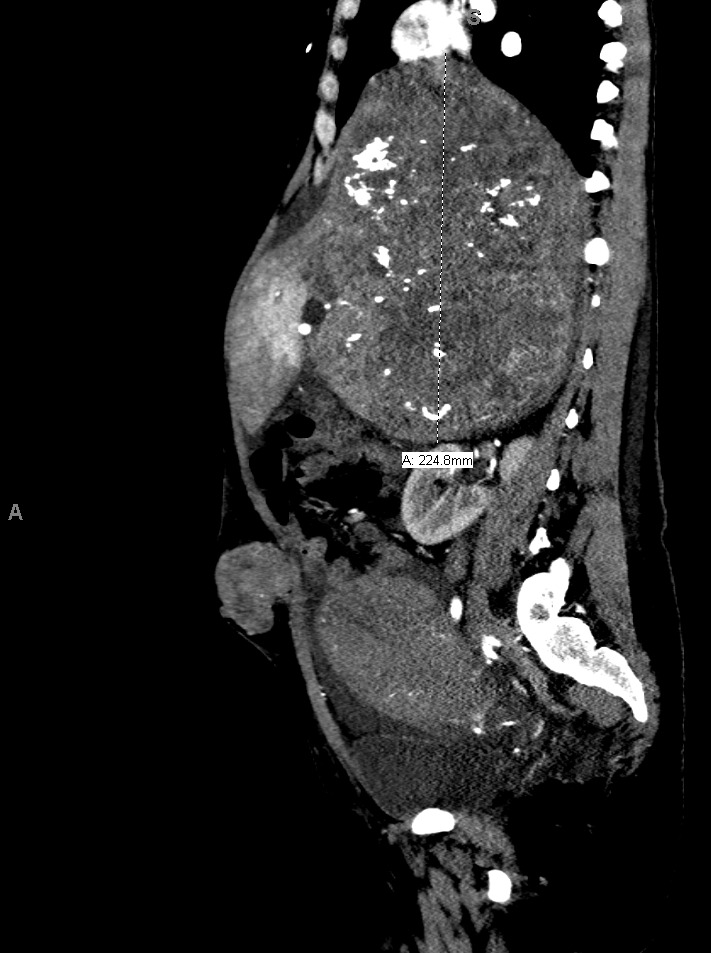

The patient delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery at 37 weeks gestation. Her tachycardia persisted postpartum with heart rates exceeding 140 beats per minute, still of unexplained etiology. She developed a leukocytosis within the normal postpartum range but remained afebrile and without fundal tenderness. Due to increasing suspicion for malignancy, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained, which showed a 19.0 x 17.7 x 22.5 cm heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue retroperitoneal mass with internal calcifications (Figures 1 and 2) and heterogeneously enhancing masses of various sizes in the liver and abdominal wall concerning for metastatic GIST (Figure 3). On postpartum day six, CT angiography of the chest was performed due to persistent tachycardia in the setting of a new diagnosis of a malignancy, which showed a right anterior lower lobe segmental and subsegmental pulmonary embolus. The patient was started on therapeutic low-molecular-weight heparin and trans-thoracic echocardiography was performed, which was unremarkable.

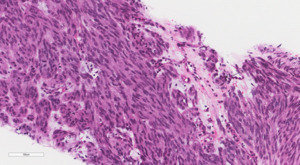

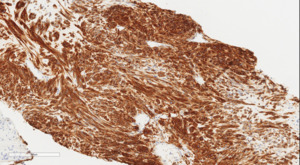

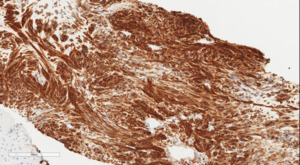

The patient was discharged home on postpartum day seven. At her surgical oncology appointment four weeks later, she continued to show signs of malnutrition with a weight loss of 20 kg compared to her intrapartum weight. An ultrasound-guided biopsy of her retroperitoneal mass confirmed the diagnosis of GIST with spindled morphology and multiple liver metastases (Figures 4 and 5). The patient’s case was reviewed in a multidisciplinary gastrointestinal tumor board, where neoadjuvant imatinib therapy was recommended. At her follow-up visit, the patient reported an increased appetite, and the size of her abdominal wall mass had decreased by approximately half. Due to an excellent initial response to imatinib therapy, this was to be continued with imaging at three-month intervals to assess her disease status; however, this plan was complicated by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, as the patient traveled oversees and was unable to return for several months. She did continue to take imatinib without difficulty during this time period.

After returning eight months later, the patient presented with pre-syncopal episodes and was found to have a hemoglobin of 5.9 g/dL. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed multiple centrally necrotic masses within the abdomen and active bleeding from her retroperitoneal mass. Interventional radiology attempted an embolization procedure, but were unsuccessful. Palliative radiation therapy to the abdomen was initiated, but after the first dose she became short of breath with weakness and hypotension. An emergent CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained, which showed multiple bowel perforations with free air and dependent fluid in the pelvis. The decision was made to proceed with medical management as the patient did not desire hospice and was too unstable for surgery. Unfortunately, her condition continued to deteriorate, and she died the following evening.

3. Discussion

Malignancy in pregnancy presents several unique challenges: (1) symptoms of malignancy such as nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and breast changes often overlap with typical symptoms of pregnancy; (2) clinicians may be hesitant to order definitive imaging in pregnancy out of concern for fetal compromise; and (3) laboratory values may be of decreased utility as some abnormalities may be confounded by normal physiologic changes of pregnancy (Salani, Billingsley, and Crafton 2014). Physicians are often forced to rely on small, retrospective studies for guidance, and the diagnosis and treatment of a pregnancy-associated malignancy requires a careful assessment of the risks and benefits to both maternal and fetal well-being (Salani, Billingsley, and Crafton 2014). GIST is rarely diagnosed during pregnancy, and the means of detection is highly variable, with several cases identified due to the patient measuring large for gestational age or as a result of persistent unexplained abdominal pain, while another patient presented with lethargy, dizziness, and abdominal fullness (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). Our case represents only the second reported instance of a primary or recurrent GIST diagnosed in the postpartum period, and thus management guidelines for this scenario are nonexistent.

Our patient presented with several unique challenges that delayed the diagnosis of a cancer recurrence. First, she presented late to prenatal care at 34 weeks gestation and delivered less than three weeks later. The superficially palpable abdominal mass appreciated at her initial visit was seemingly confirmed on abdominal ultrasound to be a benign leiomyoma, but was later revealed to be an extra-uterine soft tissue metastasis (Figure 3). GIST during pregnancy is often discovered due to size-greater-than-dates, but in the case of our patient it was difficult to arrive at an accurate estimation of either, because the patient did not know the date of her last menstrual period, and because it was believed that she had an enlarged, fibroid uterus. Additionally, because the patient’s initial surgery was done internationally, the operative report and her medical records were not attainable for review, making it difficult to assess her risk for recurrence. She did, however, present with diminished appetite and weight loss in the third trimester, which is never normal and has been associated with fetal growth restriction and poor perinatal outcomes (Mola, Kombuk, and Amoa 2011). Her cachexia and early satiety were later explained by mass effect from the tumor compressing her stomach. Following neoadjuvant imatinib therapy, the patient’s tumor initially decreased in size with significant improvement in her appetite and nutritional status; however, this response was complicated by tumor necrosis with significant intra-abdominal bleeding, as well as by multiple bowel perforations, which ultimately led to her death.

Malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a pregnant women presenting with size-greater-than-dates or with an abdominal mass, especially when associated with unexplained weight loss, poor appetite, and abnormal vital signs. Extra consideration should be given to the possibility of a recurrent GIST in a patient with a prior history of a GIST, as the recurrence rate is high without continued maintenance therapy. Following the diagnosis, delivery at 35 to 37 weeks gestation is recommended, and this is often accomplished via Cesarean delivery (Zarkavelis, Petrakis, and Pavlidis 2015). Due to the rarity and complexity of a cancer diagnosis during pregnancy, management utilizing an interdisciplinary team is recommended and has been associated with optimal outcomes.

Disclosures

Kasey Shepp has nothing to disclose. Thomas Paterniti has nothing to disclose. Diana Kozman has nothing to disclose. Elizabeth Martin has nothing to disclose. Renee Page has nothing to disclose.

Disclosure of Funding

We have received no funding for this paper.

Disclosure of Financial Support

We have received no financial support for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We have nothing to acknowledge.

Individual Author Contribution

Each author actively participated in the writing, editing, and approval of the final version of this manuscript. No authors have a financial or other conflict of interest. This report is not under consideration elsewhere, nor will it be submitted elsewhere until a final decision is made. The lead author (myself) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Institutional Review Board and Patient Consent

The institutional board of Augusta University Medical Center has deemed single patient case reports exempt from review. No persons were named in the acknowledgements. Written consent has been obtained from the patient described in this case and is filed with our records. The patient was also provided a copy of the final manuscript and given a chance to ask questions about it.