Introduction

During the past 2 decades, bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (BHRT) has become increasingly popular (Santoro et al. 2016). In 2002 the Women’s Health initiative (WHI) caused significant confusion and apprehension among both women and physicians (Hersh, Stefanick, and Stafford 2004). This created interest in potential alternatives to traditional hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Today, multiple FDA-approved transdermal formulations are available, including patches, rings, and gels or lotions (Files and Kling 2020). Further, outside the realm of HRT explored by the WHI, numerous studies have shown that women with Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder (FSIAD) formerly known as Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD) benefit from testosterone replacement (Parish et al. 2021; Shifren et al. 2006; Panay et al. 2010).

Understanding the regulatory landscape of compounded hormone preparations and compounding pharmacies is essential to interpreting the clinical relevance of pellet therapy. After all, compounding pharmacies are the most likely source of compounded hormonal therapies – an industry that generated $1.3-1.6 billion in 2013-14 alone (3204 2013; Pinkerton and Santoro 2015). Because compounded formulations, including pellets, are often scrutinized for safety and quality, outlining the FDA’s oversight provides context for why direct comparisons with other compounded routes of administration are necessary. There is a pervasive misconception that compounding pharmacies are completely unregulated by the FDA. In fact, there are longstanding regulations at the Federal and State levels. In 2014 the Drug Quality and Security Act, gave the FDA additional powers to regulate compounding pharmacies, including establishing the requirement of compliance with current good manufacturing practice (CGMP), similar to what is required by the pharmaceutical industry. This required compounding pharmacies to improve testing for their manufactured processes. GMP imposes processes to assure purity, potency, and quality, in addition to improved sterility protocols (3204 2013) FDA-approved hormone preparations include a label detailing risks and benefits, however, compounded formulations are not required to provide package safety inserts. Thus, health care providers who utilize compounded hormone preparations must be diligent in providing this information to their patients. According to two recent surveys (Harris and Rose) up to 2.5 million US women aged 40 years or older may use compounded hormone therapy accounting for 28% to 68% of hormone prescriptions (Pinkerton and Santoro 2015).

In addition to the abundance of published literature supporting the use of testosterone in women with FSIAD, there is also a growing body of evidence that androgens affect mood, energy, psychological well-being, bone density, muscle mass and strength, and adipose tissue distribution (Bachmann et al. 2002). In women, an imbalance in androgen biosynthesis or metabolism may have undesirable effects on all of these domains. Despite the mounting evidence of the benefits of exogenous testosterone in women, there are currently no FDA approved formulations while there are over 30 FDA approved testosterone preparations for men.

Testosterone can be administered via several routes, including transdermal, oral, intramuscular, and subcutaneous pellet implants. Compounded pellets were first described in 1949 to treat menopausal symptoms (Greenblatt and Suran 1949). Subcutaneous testosterone pellet therapy has been used worldwide for decades. Practitioners have found this delivery method to provide safe and effective therapy without the fluctuations in blood levels often seen after transdermal or intramuscular administration (Shifren et al. 2006; Panay et al. 2010). Subcutaneous pellets are similar in size to a grain of rice and are most commonly placed in the hip, buttock, or flank. The pellets then release hormones (estradiol and testosterone) into the blood stream over 3-6 months. While there are multiple peer-reviewed publications demonstrating that subcutaneous pellet therapy in women may be safe and effective (G. S. Donovitz 2021; G. Donovitz et al., n.d.; Glaser, York, and Dimitrakakis 2019, 2011; Glaser and Dimitrakakis 2013), society consensus papers and a recent ACOG Practice Bulletin recommend only FDA-approved transdermal administration, unless there is a rare allergy or contraindication to using such. They also strongly discourage pellet placement, citing a lack of safety data and concern about the inability to remove a pellet once it is placed (Davis et al. 2019; “Compounded Bioidentical Menopausal Hormone Therapy: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 6” 2023). To date there are no published studies comparing transdermal menopausal hormone therapy to subcutaneous pellet HRT.

The aim of this study was to determine if subcutaneous bioidentical estradiol and testosterone pellet therapy, dosed according to the Biote® method, resulted in symptomatic improvement of menopausal vasomotor symptoms and corresponding increases in serum estradiol and testosterone levels when compared to compounded transdermal lotion HRT.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (6100 Merriweather Dr., Suite 600, Columbia, MD 21004). It represents a retrospective observational cohort study of women experiencing menopausal symptoms and FSIAD who underwent subcutaneous bioidentical pellet HRT containing estradiol and testosterone or compounded bioidentical transdermal lotion with estradiol and testosterone.

Adequate power was ensured before the collection of patient data. The Herbal Alternatives for Menopause (HALT) study compared reduction in menopausal hot flashes among multiple botanical treatments, estradiol, and placebo. They found an approximately 66% reduction in hot flashes in the group taking FDA-approved HRT compared to a 28% reduction in women taking placebo (Reed et al. 2008). We hypothesize that the conventional bioidentical transdermal gel HRT group will have a 50% reduction in hot flash severity (better than placebo, but not as high as conventional HRT), and the pellet HRT group will have a 66% reduction in hot flash severity. Assuming 90% power and an alpha of 0.05, 195 women are needed in each group to detect a significant difference in hot flashes between groups.

This retrospective cohort consisted of female patients seeking gynecologic care for menopausal symptoms as part of routine clinical care from a single board-certified Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic surgeon who started bioidentical HRT between 2018-2021. Inclusion criteria included the ability to complete questionnaires prior to starting HRT (collected as part of routine clinical care) and being up-to-date on preventive health measures including current, appropriate breast cancer screening. Exclusion criteria included 1) active breast or gynecologic cancer, 2) a history of breast or gynecologic cancer, 3) Any history of VTE, 4) untreated hypertension, 5) the use of another form of HRT within the last 12 months, and 6) current undiagnosed vaginal bleeding at the time of HRT initiation. The first 200 women treated with pellet HRT and the first 204 treated with lotion HRT who met inclusion/exclusion criteria during this time-period were included in the analysis. As standard-practice, women with a uterus were also prescribed micronized progesterone (MP) for endometrial protection.

All patients completed a standardized menopausal symptom and adverse event assessment at each follow up visit. Patients completed a validated Menopause Symptoms Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (MS-TSQ) at least one year after starting treatment as part of long-term follow-up. The MS-TSQ includes eight items, six assessing satisfaction with the treatment’s ability to control specific menopausal symptoms; one addressing side effects or treatment tolerability; and one global treatment satisfaction item. This was accomplished by a retrospectively obtained questionnaire given to patients at ≥1 year after HRT initiation at a follow-up appointment with the primary author.

Initiation of HRT

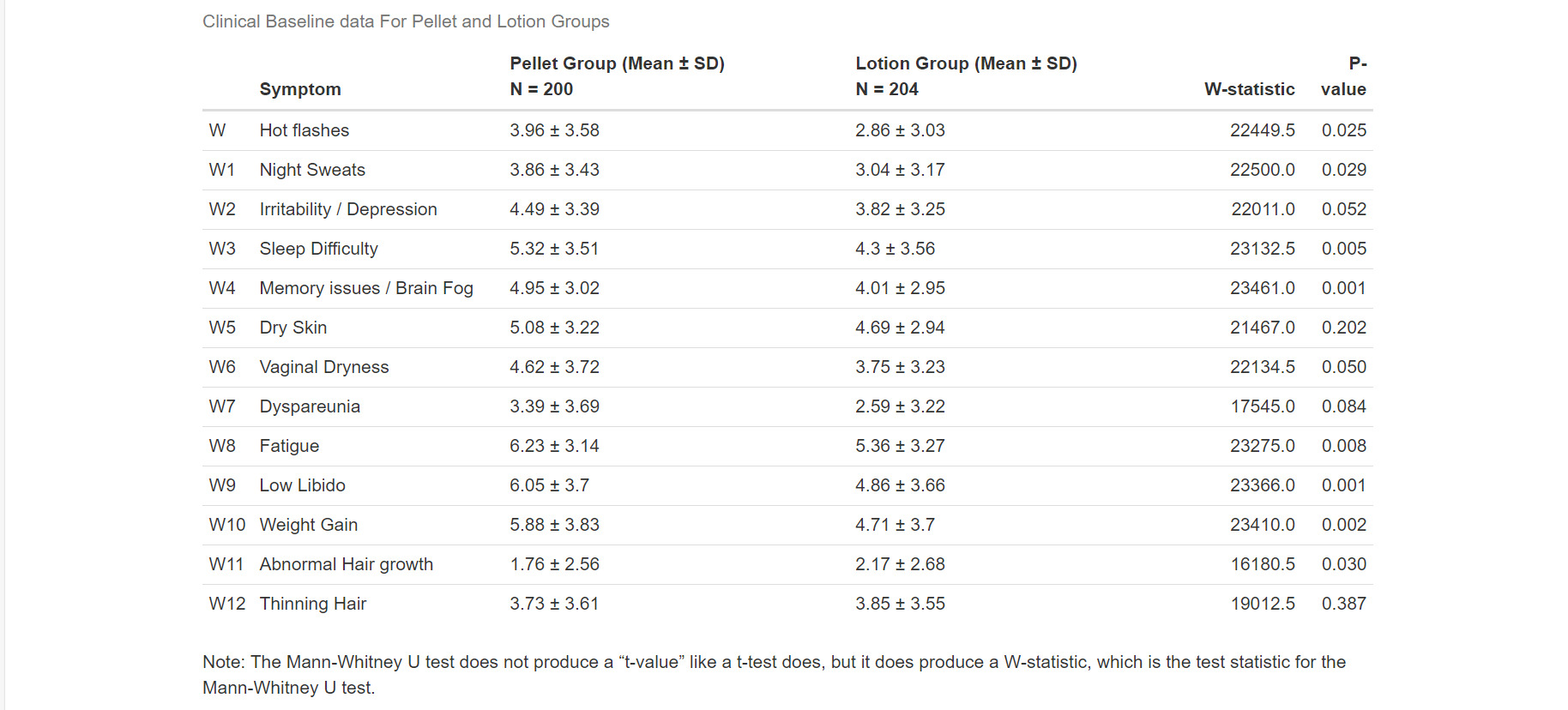

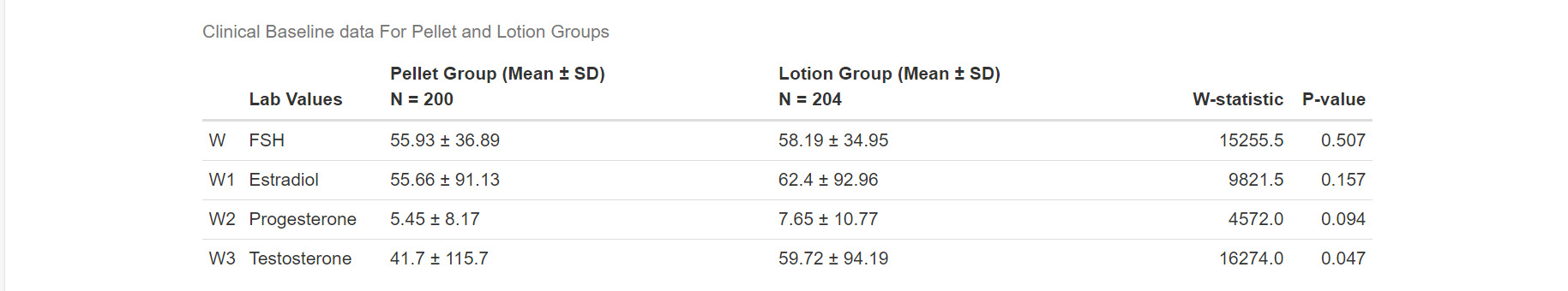

At baseline (prior to starting HRT), all patients completed a non-validated menopausal symptom questionnaire. They were asked to rank their symptoms on a 10-point scale (0= no symptoms and 10= severe symptoms). Items assessed included hot flashes, night sweats, irritability/depression, trouble sleeping, memory/brain fog, dry skin, wrinkling, vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, fatigue/low energy, and low sex drive. Patients also self-reported symptom severity of the following HRT-associated possible adverse effects: weight gain, acne, abnormal hair growth, thinning hair, and palpitations/jitteriness. Baseline laboratory results including Vit D, Vit B12, Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Estradiol, Progesterone, Testosterone, Total Cholesterol, and HDL/LDL were obtained.

Women were counseled regarding different HRT regimens including FDA approved HRT, bioidentical pellet (estradiol and testosterone) and compounded bioidentical transdermal lotion formulations containing estradiol and testosterone. Which HRT regimen patients were given was an individual choice after shared decision making. Those randomized to the Pellet formations received follow up at 6 weeks and those who received the pellet formulation received follow up at 10 weeks (as below). The 6-week and 10-week timepoints reflect the standard clinical follow-up intervals in the primary author’s practice.

Women who chose pellet HRT were dosed according to a proprietary algorithm and underwent pellet placement in clinic. Based on the algorithm, Pellet doses ranged from 6-18mg for estrogen and from 50-175mg for testosterone. Repeat laboratory values were obtained four weeks after pellet placement as per the algorithm. Symptom were reassessed in the office 6 weeks following initial pellet placement. Patients were evaluated for potential re-dosing at this time based on symptoms and repeat laboratory results. After optimal dosing was achieved, pellets were placed every 4 months for maintenance. If symptom control diminished, testosterone-containing pellets were placed every 3-months and estradiol pellets every 6-months.

Patients who chose the bioidentical transdermal lotions were instructed to apply the compounded lotion containing estradiol and testosterone to skin behind one knee every night at bedtime. This area is selected because the skin is thought to be thinner and promotes better absorption. Laboratory values were obtained first thing in the morning, about 8-10 hours after the most recent dose, approximately 10 weeks (+2 weeks) after starting therapy. Symptoms were assessed at follow-up visits 2 weeks after labs were obtained, and lotion dosing was adjusted based on laboratory values and symptoms. If symptom control remained inadequate, repeat laboratory values were obtained and adjustments made every 2-3 months until symptoms improved. Initial lotion dosage contained estradiol 1.5 mg and testosterone 7 mg. The amount of testosterone was only increased if symptom improvement had not occurred at 1 and 2 months after starting the lotion therapy; however, serum levels were maintained to a level of 250 ng/dL or less.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was improvement in self-reported vasomotor symptom severity as measured by frequency of menopausal hot flashes, after initial pellet dosing versus transdermal bioidentical HRT. The primary outcome was assessed at 6 (+/- 2) weeks in the pellet group and 10 (+/- 2) weeks in the lotion group. Secondary outcomes included changes in self report of other menopausal symptoms and adverse events at similar timepoints. Serum hormone levels were also compared between the two groups. Finally, using the MS-TSQ (which was obtained as a part of the standard clinical practice of the primary author), long-term treatment satisfaction was compared between groups as well as the percentage of patients still using their selected treatment.

Sample Size Calculation

The HALT study (Reed et al. 2008) compared reduction in menopausal hot flashes among multiple botanical treatments, estradiol, and placebo. They found an approximately 66% reduction in hot flashes in the group taking FDA-approved HRT compared to a 28% reduction in women taking placebo. We hypothesized that the bioidentical transdermal lotion HRT group would have a 50% reduction in hot flash severity, and the pellet HRT group would have a 66% reduction. Assuming 90% power and an alpha of 0.05, 195 women would be needed in each group to detect a significant difference in hot flashes between groups.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Proportions of variables were compared using Fisher’s exact and chi-squared tests. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Mean hot flash scores (0-10) were compared between HRT groups using Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Chi Squared test for categorical variables. R version 4.3.0 was used to perform the data analyses.

Results

Demographics

Women receiving pellet therapy were slightly older than those receiving lotion therapy (64 years vs 60 years, p<0.0001). Demographic characteristics were otherwise similar between groups (Table 1).

Change in Symptoms

Women on pellet therapy experienced significantly greater improvement in vasomotor symptoms (−2.08 vs −1.03, p<0.003). Further, the pellet group also displayed significantly greater improvement in night sweats (p=0.0016), sleep difficulty (p=0.0002), memory issues (p=0.001), dry skin (p=0.009), vaginal dryness (p=0.000), dyspareunia (p=0.010), fatigue (p=0.001), weight gain (p=0.04), and low libido (p=0.0002). No significant difference was seen between groups in abnormal hair growth (0.25), depression (p=0.059), and thinning hair (0.39). (Table 4). Women on pellet therapy had larger increases in serum testosterone and larger decreases in FSH compared to women using lotion (Table 3, Table 5)).

Adverse Events

There were no differences in reports of adverse symptoms between groups (Table 2), including weight gain, acne, abnormal hair growth, thinning hair, and palpitations/jitteriness,

Menopause Symptoms Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire

Overall, there was a 51% rate of completion of the Menopause Symptoms Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire at ≥1 year follow-up appointment. Women in the pellet group were more likely to participate in this follow up compared to women in the lotion group (61% versus 41% p=0.0002) (Table 6). Women in the pellet group were also more likely to continue that therapy compared to those who started lotion therapy (76% vs 68% p=0.019) and more likely to report that HRT treated their symptoms (89% vs 78% p<0.001). Satisfaction related to HRT was high in the cohort (84%) with no differences between formulations (pellet 85% vs lotion 80% p=0.739) (Table 7, Table 8).

Women who continued treatment with either modality (76with pellet and 59 with lotion) reported high levels of satisfaction in symptom control according to the MS-TSQ with no differences seen between the two groups (Table 7).

Discussion

This is the first study that compares transdermal estradiol and testosterone lotion to subcutaneous estradiol and testosterone pellet therapy. In this study, women on pellet therapy had hot flash symptom relief as well as a greater improvement in all other domains with the exception of depression, abnormal hair growth, and thinning hair when compared to the women in the transdermal group. Additionally, in the 2 groups, there were no differences in adverse symptoms related to estradiol or testosterone. The larger increases in serum testosterone and corresponding decreases in FSH among pellet users suggest a more robust suppression of menopausal endocrine changes. Although serum testosterone levels exceeded typical physiologic ranges in some pellet users, this was not associated with increased adverse events, and may help explain the greater symptomatic relief observed, particularly for vasomotor and energy-related symptoms. Further, fifty-one percent of patients completed long-term follow up with a validated questionnaire, which revealed good symptom satisfaction in both groups. However, women on pellet therapy were more likely to participate in the follow up questionnaire and were also more likely to continue their initial mode of treatment compared to those in the transdermal group.

Hormone replacement therapy continues to be clinically challenging, and there is significant controversy regarding indications, dosing, route of administration, and the assessment of risk versus benefit.

Multiple societies’ consensus statements have consistently stated that compounded hormones should not be prescribed and that only FDA-approved preparations should be used (Davis et al. 2019). This has also been published in a recent ACOG practice bulletin (“Compounded Bioidentical Menopausal Hormone Therapy: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 6” 2023). These same publications state that subcutaneous pellet hormone administration should be avoided. An extensive literature review reveals only one peer-reviewed publication suggesting that FDA- approved HRT had fewer side effects than bioidentical pellet HRT (Jiang et al. 2021). This retrospective chart review compared 539 patients on pellet hormone therapy with 155 on FDA-approved regimens and concluded that the pellet group sustained more androgenic side effect. However, only 4.5% of the patients in the FDA group received any testosterone supplementation while 99% of patients in the pellet group received testosterone supplementation. Additionally, the estrogen-related side effects were not necessarily attributable to the mode of administration.

A recent study looked at long-term testosterone pellets therapy in women with low libido. Patients were followed for a 5-year span at two different pellets doses and there were no significant changes in testosterone trough levels over the treatment duration. They also noted no statistically significant change in hematocrit levels or systolic blood pressures with a very low risk of side effects (Reddy et al. 2023). Many other studies report good clinical outcomes with an acceptable safety profile in women receiving subcutaneous pellet HRT therapy (G. S. Donovitz 2021; G. Donovitz et al., n.d.; Glaser, York, and Dimitrakakis 2019, 2011; Glaser and Dimitrakakis 2013).

The authors agree with consensus statements and the ACOG Bulletin regarding the need for higher quality long-term studies evaluating bioidentical hormone replacement in general and, specifically, the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous pellet therapy.

However, there continues to be a negative narrative regarding pellet administration based on opinions and concerns that have not been substantiated in the current published literature. For example, a recent clinical commentary by Dunsmoor-Su et al., asserts that the authors frequently care for women who have significant complications from pellets, and on this vague basis, dissuades readers from using these products. This commentary also misrepresented Biote (Dunsmoor-Su, Fuller, and Voedisch 2021).

Another controversial area revolves around the clinical utility of testosterone blood levels. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) practice guidelines make the point that the testing testosterone levels in women is not diagnostic and should be used only to establish a baseline and monitor therapy (Davis et al. 2019). The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) concurs, stating that hormone testing in general has very limited use in menopause and is usually employed to evaluate for poor absorption in women with no symptom relief and to avoid supraphysiologic levels (The North American Menopause Society 2014). These opinions are not new. In 2002, he the Princeton Consensus Group published their opinion stating that there are no age-specific normal testosterone values established for women (Bachmann et al. 2002). A recent ACOG Committee opinion states that testosterone concentrations should be maintained in the physiologic premenopausal range of 20-80 ng/dL (“Compounded Bioidentical Menopausal Hormone Therapy: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 6” 2023). Our study revealed that total testosterone levels at 206.4 ng/dL in the pellet group and 54.1 ng/dL in the transdermal group showed no significant difference in side effects. We suspect that the pellet patients had their blood drawn when testosterone levels were peaking while the transdermal patients may have been evaluated when their testosterone levels were at trough levels.

The strengths of the study include the use of a standard dosing schedule for both the administration of testosterone and estrogen pellets. We also utilized a standard supplier of both the pellets and the transdermal therapy. Both formulations were produced by reputable establishments well known to the practice. Weaknesses of the study are its retrospective study design, conferring the risk of selection bias from both the prescribers and the patients. As the distribution of Pellet versus lotion was based on patient choice and not based on a randomization scheme, selection bias could have affected the results of this study. Further weaknesses were found in the follow-up after the initiation of HRT. The follow up time points of 6 weeks in the pellet group and 10 weeks in the lotion group (which became the primary outcome of this study) were due to the timing of follow up in the primary author’s clinic and as such could not be standardized. The lack of assessment of sexual desire prior to and during treatment would have been helpful in informing treatment success in these populations and the lack of this data is a further limitation. Additionally, long-term follow-up consisted of a retrospectively obtained questionnaire completed at follow-up appointment ≥1 year after HRT initiation. This questionnaire was completed by only half of the cohort - another weakness of this study. However, the instrument used for long term follow up is validated and proved feasible to administer in this setting.

Conclusion

In the absence of any FDA-approved testosterone preparation for women, we must provide alternative options for women suffering from treatable menopausal conditions. There is growing evidence to reassure physicians and patients that bioidentical, pellet-administered HRT when used in an appropriate fashion is safe and effective. More importantly, as physicians and scientists, we must promote open and honest dialogue and allay prevalent but unfounded fear of hormonal therapies. Bioidentical HRT including estrogen and testosterone, administered by subcutaneous pellets, improves quality of life for women with menopausal symptoms without significant risk of adverse events in this study. Further studies confirming these findings with better long-term follow-up and in the form of randomized controlled trials are urgently needed.

Authorship Confirmation/Contribution Statement

All Authors contributed to this work. Greg Bailey acted in conceptualization and methodology, resource and funding acquisition, project administration, investigation, supervision, validation, and writing. Rodger Rothenberger acted in data curation, investigation, and writing.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (6100 Merriweather Dr., Suite 600, Columbia, MD 21004). Approved 01/13/2023. Reference number ((Pro00068806). All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and have been approved by this Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the invaluable contributions of Danielle Solimando-Torres, Henry Braddy, and Ella Braddy. We would also like to thank the peer reviewers for their suggestions, opinions, and thoughtful consideration

Financial Support/Funding

This study was funded by an unrestricted research grant from the Foundation for Female Health Awareness. There is no Associated grant number for this grant. www.femalehealthawareness.org

Conflict of interest/financial disclosure

Greg Bailey, MD and Rodger Rothenberger, MD have no conflicts of interest.