Key Findings

-

Indications for dilation and curettage in this patient’s case included suspected cesarean scar pregnancy, noted on early ultrasound; a diagnosis of missed abortion; and the risk of hemorrhage without active management

-

Indication for exploratory laparotomy was significant blood loss of approximately 1500 milliliters during dilation and curettage. Given prior and intraoperative ultrasound findings, providers in the case were concerned for morbidly adherent placenta with possible uterine invasion at the level of the cesarean scar. Bleeding was not resolved with more conservative measures, including attempted foley tamponade.

-

During exploratory laparotomy, providers were able to confirm that the uterus and adjacent structures were intact without damage. The patient’s hemorrhage was then able to be controlled through uterine artery embolization by interventional radiology.

Teaching Points

-

Cesarean scar pregnancy and placenta accreta spectrum are two conditions that may represent the same abnormalities of placental invasion at different times of gestation.

-

These pathologies carry profound risk of hemorrhage – even in the first trimester of pregnancy.

-

Additional research is needed to evaluate the best methods for bleeding prevention and management in patients with cesarean scar pregnancies and placenta accreta spectrum in early pregnancies. Ideally, such methods would allow for preservation of fertility if the patient so desired.

-

Providers performing dilation and curettage should remain cognizant of the risk for significant bleeding due to cesarean scar pregnancy and accreta spectrum pathology in any patient with risk factors for accreta.

-

Cesarean scar pregnancy and placenta accreta spectrum pathologies can be missed in early pregnancy losses and misdiagnosed as inevitable abortions due to lower uterine segment placement.

CASE

Background

Cesarean scar pregnancy is a condition of abnormal implantation whereby the embryo implants into the myometrium of a previous cesarean scar. The placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is a term applied to classify disorders of overly adherent placental attachment at a previous cesarean scar. CSP, diagnosed in the first trimester, is likely a precursor to PAS, typically diagnosed later in pregnancy. CSP and PAS are two conditions that may represent the same abnormalities of placental invasion at different times of gestation. CSP is likely a precursor to PAS and typically occur in pregnancies with a maternal history of uterine surgery, cesarean surgery, myomectomy, and previous dilation and curettage (D&C). As a result of such uterine procedures, a focal absence of the normal decidua basalis can occur. This creates an environment that may allow trophoblastic invasion to the damaged area and exposed myometrium. Consequently, this can lead to abnormally deep placental anchoring villi and trophoblastic infiltration. Such pathologies ultimately risk severe hemorrhage and resultant maternal morbidity and mortality. PAS severity ranges from implantation through the full thickness of the endometrium to invasion beyond the myometrium and into structures adjacent to the uterus, including bladder, rectum, and the peritoneal walls. The paramount complication to be aware of in cases of CSP and PAS alike is hemorrhage.

Much of the current research on disorders of placental attachment focuses on diagnosis and management of these conditions in the late second and third trimesters. While this is invaluable, there remains a guidance gap on how to approach abortive cases complicated by PAS and CSP in the first trimester. These early presentations, though rare, can similarly result in life-threatening hemorrhage that demands rapid, skilled intervention to mitigate.

Methods

This case report, diagnosed in early 2025, includes the history, presentation, and rapidly evolving clinical management of a first-trimester missed abortion in a pregnancy complicated by CSP versus PAS. A separate chart review was performed on this case after the patient’s post-hospital clinic follow-up to monitor for any complications in the month succeeding her discharge.

Results

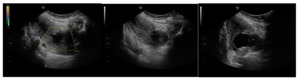

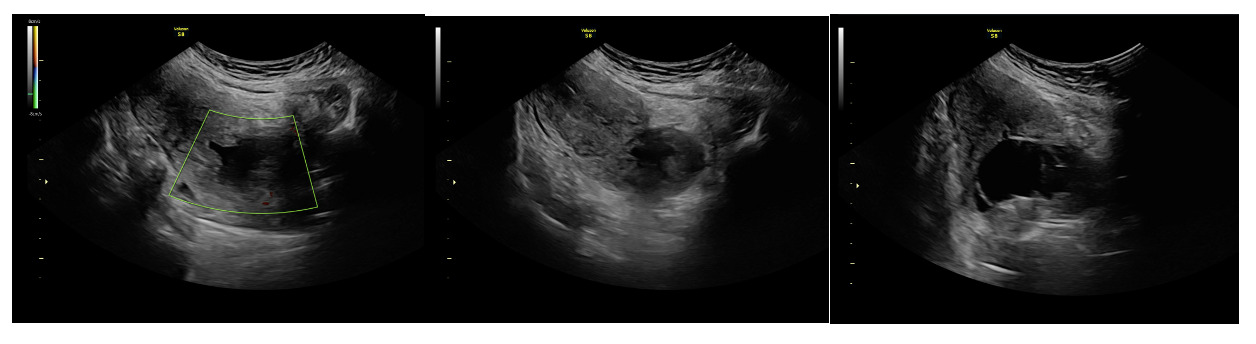

A 31-year-old gravida 2 para 1001 at 13 weeks and 6 days gestation by a 7-week ultrasound presented to ULH for surgical management of a missed abortion in the setting of suspected CSP versus PAS. The patient had previously been seen at an outside hospital emergency room for concerns of bleeding and pelvic pain. Ultrasound workups for these concerns were significant for viable intrauterine pregnancy and moderate subchorionic hemorrhage superiorly, grossly measuring 5 cm at the largest dimension. Two weeks after her initial emergency department (ED) visit, the patient was seen in our practice’s general obstetric clinic. A first trimester ultrasound was performed at this time and again demonstrated a 5 cm subchorionic hemorrhage (Figure 1). At this time, concern for CSP versus PAS was also noted, and the patient was advised to return for a follow-up scan. When the patient returned for further evaluation of placental pathology, ultrasound revealed fetal demise with absent fetal cardiac activity (Figure 2). Following discussion with the maternal fetal medicine (MFM) provider, the patient ultimately elected for surgical evacuation of the products of conception to mitigate spontaneous bleeding risks in the setting of CSP versus PAS.

On admission for planned D&C, consents for laminaria placement, suction dilation and curettage under ultrasound guidance, possible uterine artery embolization, and possible hysterectomy were discussed and signed. The patient then underwent successful placement of a large and a medium-sized laminaria without complication. She subsequently underwent suction D&C with ultrasound guidance (Figure 3). Despite the prophylactic placement of 400 micrograms of rectal misoprostol and the administration of 20 units of Pitocin in IV fluids at the start of the case, the patient experienced significant hemorrhage during the procedure with an estimated blood loss of 1500 mL. Intraoperative findings raised concern for uterine rupture (Figure 4). A Foley balloon inflated with 30cc of saline was placed for attempted intrauterine tamponade (Figure 5), and a brisk blood loss of 500 mL immediately filled the foley catheter bag. Vaginal packing and intramuscular methergine were given as additional attempts to control the bleeding, but the patient’s hemodynamic status deteriorated intraoperatively. This necessitated volume resuscitation and transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells. An emergent exploratory laparotomy was then performed to identify the source of the bleeding to repair or perform hysterectomy. A thorough survey of the uterus, adnexa, and adjacent pelvic structures revealed no overt source of bleeding, uterine rupture, or organ invasion with the uterine and bladder serosa intact. No hemoperitoneum was found. Further inspection revealed no additional blood loss beyond the 500 mL blood loss in the foley bag. Blood loss was stabilized, and the patient became hemodynamically stable. The abdomen was closed, and the patient was transferred to interventional radiology for uterine artery embolization, which additionally controlled the hemorrhage. Following embolization, the patient was stable and extubated without issue.

On postoperative day 1, the intrauterine Foley catheter balloon was removed without recurrence of bleeding. The patient recovered well, resumed a regular diet, ambulated independently, and opted for Nexplanon insertion for contraception. By discharge on postoperative day 3, she reported only scant vaginal bleeding, remained hemodynamically stable, and required no further transfusion. At an outpatient follow-up appointment two weeks after her hospitalization, the patient reported that she was recovering well. It was recommended that repeat imaging of the patient’s uterus occur within the next 6 months, and that the patient should schedule an MFM preconception consultation prior to any attempt at future pregnancy.

Discussion

This case highlights the rare but serious complication of significant hemorrhage during first trimester D&C in a patient with suspected CSP versus PAS pathology. Although placenta accreta is typically associated with second and third-trimester morbidity, its presence in early pregnancy as CSP poses an equally significant risk for life-threatening hemorrhage. Our patient’s course highlights several key considerations. First, pregnancies with overly adherent attachments - regardless of age of gestation - can present with significant hemorrhage that is unresponsive to routine uterotonics and tamponade techniques. Second, preoperative recognition of PAS, while critical, does not eliminate the potential for intraoperative instability, necessitating a multidisciplinary team that includes surgical, anesthetic, and interventional radiology support. Finally, this case illustrates that fertility-sparing hemorrhage management such as uterine artery embolization is possible in select cases with rapid diagnosis and coordinated care.

Conclusion

Cesarean scar pregnancies and placenta accreta spectrum are conditions of overly-adherent placental pathology that has become increasingly common as the incidence of uterine procedures, particularly cesarean births, has risen. Intrauterine procedures risk disruption of the endometrial-myometrial interface, creating “abnormal” surfaces for potential future embryos to attach. CSP and PAS risk significant maternal morbidity and mortality as a result of hemorrhage. This risk is not limited to the time of delivery of a third-trimester pregnancy – the possibility of severe bleeding is present even in cases of first trimester pregnancies. High alert and seeking diagnosis, meticulous preoperative risk stratification, access to multidisciplinary care, and early planning for hemorrhage control are essential for optimizing maternal outcomes. Greater awareness and clearer guidelines are also needed to support clinicians in managing CSP and PAS outside of the typical gestational window.