Introduction

Early pregnancy loss, or miscarriage during the first trimester of pregnancy, is common, occurring in about 10% of clinically diagnosed pregnancies (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018). However, its prevalence does not mean it is an easy experience. Many pregnant individuals experiencing early pregnancy loss note feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression. As such, adequate time off from work after pregnancy loss may be beneficial to adequately address these mental health aspects, as well as any physical health problems that may arise during the pregnancy loss.

A shortened parental leave, previously known as “maternity leave”, after delivery has been linked to postpartum depressive symptoms (Kornfeind and Sipsma 2018). However, the link between a shorter leave after pregnancy loss and mental health has not been studied to our knowledge. Some companies have already begun offering their own internal pregnancy loss leave, with 13.2% of surveyed companies offering unpaid leave and 8.7% offering paid leave in the United States in 2020 (International Foundation of Employee Benefits Plans 2020). Despite this, many individuals note confusion about what parental leave options exist as well as stigma for taking time off (Gilbert et al. 2023). Given this increased discussion of parental leave after pregnancy loss and the mental health burden on those experiencing early pregnancy loss, it is necessary for research to investigate the impacts of parental leave on mental health after pregnancy loss. We hypothesize that patients that take parental leave after an early pregnancy loss experience less depression and anxiety than those that do not take leave.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A protocol for this retrospective cohort survey study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio under non-committee review (#2023-0402). A waiver of consent was obtained for checking patients’ charts for initial eligibility, and an additional waiver of consent was obtained for the anonymous survey. The study exposure variable was access to parental leave after first trimester pregnancy loss, and the outcome variables measured were related to mental health and support. Parental leave was defined as any time taken off of work after the pregnancy loss, whether it was through a defined parental, bereavement, or medical leave.

An initial study pool was created of patients that received ICD-10 diagnosis codes of O00-O08 and/or CPT billing codes of 59414, 59812, 59820, 59830, 59840, 59850-59852, 59855-59857, 59870, S0190, S0191, or S0199 in 2022. After determining which of these patients were eligible, all eligible patients were sent an invitation to take the anonymous survey on July 7, 2023 through the electronic medical record. Communications emphasized the survey was anonymous and optional, with participants able to stop completion of the survey at any time. Survey data was collected over two weeks from 7 July 2023 through 21 July 2023 using Research Electronic Data Capture (RED-Cap).

Participants

Patients from the initial study pool were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: pregnancy loss at or before 12w6d in 2022 that was confirmed via ultrasound or pathology, UC Health patient, English speaking, and employed at time of pregnancy loss. The initial study pool had their charts consulted to confirm the inclusion criteria were present before the survey was sent. Patients that were diagnosed with early pregnancy loss but only received beta HCG trend testing to confirm the loss were excluded, as well as any patients diagnosed with biochemical pregnancies. Information was not collected on whether patients had a history of recurrent pregnancy loss. The final inclusion criteria of employed at time of pregnancy loss was determined during the survey.

Measures

Patients were asked 47 questions in English relating to demographics, access to professional mental health, their perceived level of support, and questions from the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) relating to depression and anxiety. The final question included a free text response for patients to provide any relevant comments if they desired. The survey was developed in partnership with two obstetrician-gynecologists specializing in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. The PRIME-MD PHQ has been validated for use in obstetrics populations, and it includes questions related to anxiety that the more common PHQ-9 does not (Spitzer et al. 2000). While the initial questionnaires ask for patients’ assessment of symptoms on a “Not at all”, “Several days”, “More than half the days”, and “Nearly every day” scale, our survey asked patients if these feelings were present on a “Yes”, “No”, and “Unsure” scale to account for the recall bias given the amount of time since the loss in 2022. As such, the scoring was adjusted to 0 for “No” or “Unsure” and 1 for “Yes”.

Statistical Analysis

The demographic data and the outcome data were compared for patients that took parental leave and those that did not take parental leave. Further analysis was also done of the subgroups of paid and unpaid parental leave.

Investigation of the continuous variables of PRIME-MD PHQ scores was conducted using an unpaired T-test. All other variables were dichotomous and used a Chi-square analysis. Generalized linear models were then used on dichotomous variables resulting in statistically significant differences to confirm the findings, though a result was only generated successfully for the perceived impact on mental health variable. No confounding variables were found. Results were considered statistically significant if probability value was <0.05.

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software (version 15.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

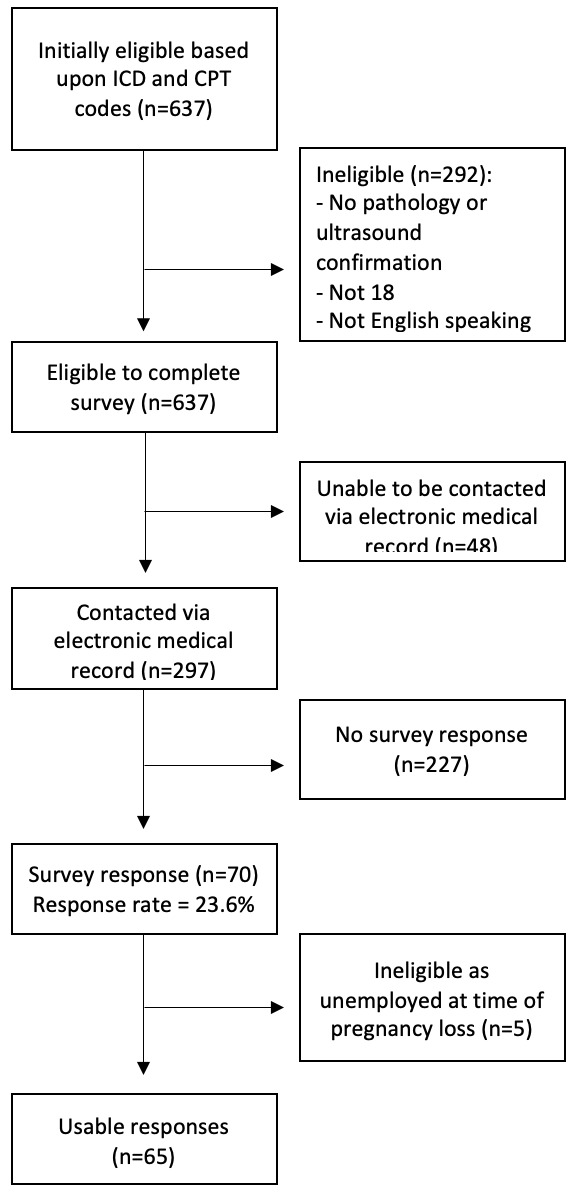

A total of 637 patients were initially identified based upon ICD and CPT codes. Two hundred and ninety-two patients were ineligible for recruitment due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. Of the 345 patients (49%) confirmed as eligible, 297 (47%) were able to be contacted through the electronic medical record. Ultimately, 70 patients completed the survey for a response rate of 23.6% among eligible contacted patients, with five taking paid parental leave, five taking unpaid parental leave, and 55 taking no parental leave (Figure 1). Five patients completed the survey that were unemployed, and their responses were excluded from the study.

The mean age of the population was 33 years (SD 5). Approximately 72.3% of patients identified as (n = 47) White/European American, 12.3% (n = 8) Black/African American, 4.6% (n = 3) Asian/Asian American, 4.6% (n = 3) Latino/a/Hispanic, 1.5% (n = 1) American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 1.5% (n = 1) Middle Eastern/North African. A majority of the patients were employed full-time (n = 54, 83.1%) and worked fully in person (n = 48, 73.8%).

The rate of parental leave in the study population of 15.4% (n = 10) was similar to the national rate of companies offering leave of 21.9% (International Foundation of Employee Benefits Plans 2020) (χ2 [1,n=65] = 0.818, p = 0.37). Of those who took parental leave, patients were evenly divided between paid (n = 5) and unpaid (n = 5) leave. The length of parental leave also varied from 1-3 days to 1-3 weeks (Table 1).

The mean modified PRIME PHQ depression score was 3.5 out of 9 (2.12 SD) for those that took parental leave compared to a statistically higher score of 5.35 (2.55 SD) (p=0.035) for those that did not take leave. This is a difference of 1.85 on a 9 point scale, which is 20.5% of the scale. These scores cannot be placed into the unmodified PRIME PHQ depression severity ranges, though these ranges increase in severity at approximately 18.5% intervals of the unmodified depression scale. Of note, the difference between paid parental leave and unpaid parental leave mean modified PRIME PHQ depression score was not a statistically significant difference (p=0.4888). There was not a statistically significant difference between modified PRIME PHQ anxiety scores for those taking parental leave and those not taking parental leave (p=0.0634), nor for paid and unpaid parental leave (p=0.5060). Additionally, there was not a statistically significant difference between panic syndrome scores for those taking parental leave and those not taking parental leave (p=0.0961), nor for paid and unpaid parental leave (p=0.3466) (Table 2).

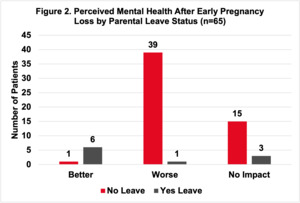

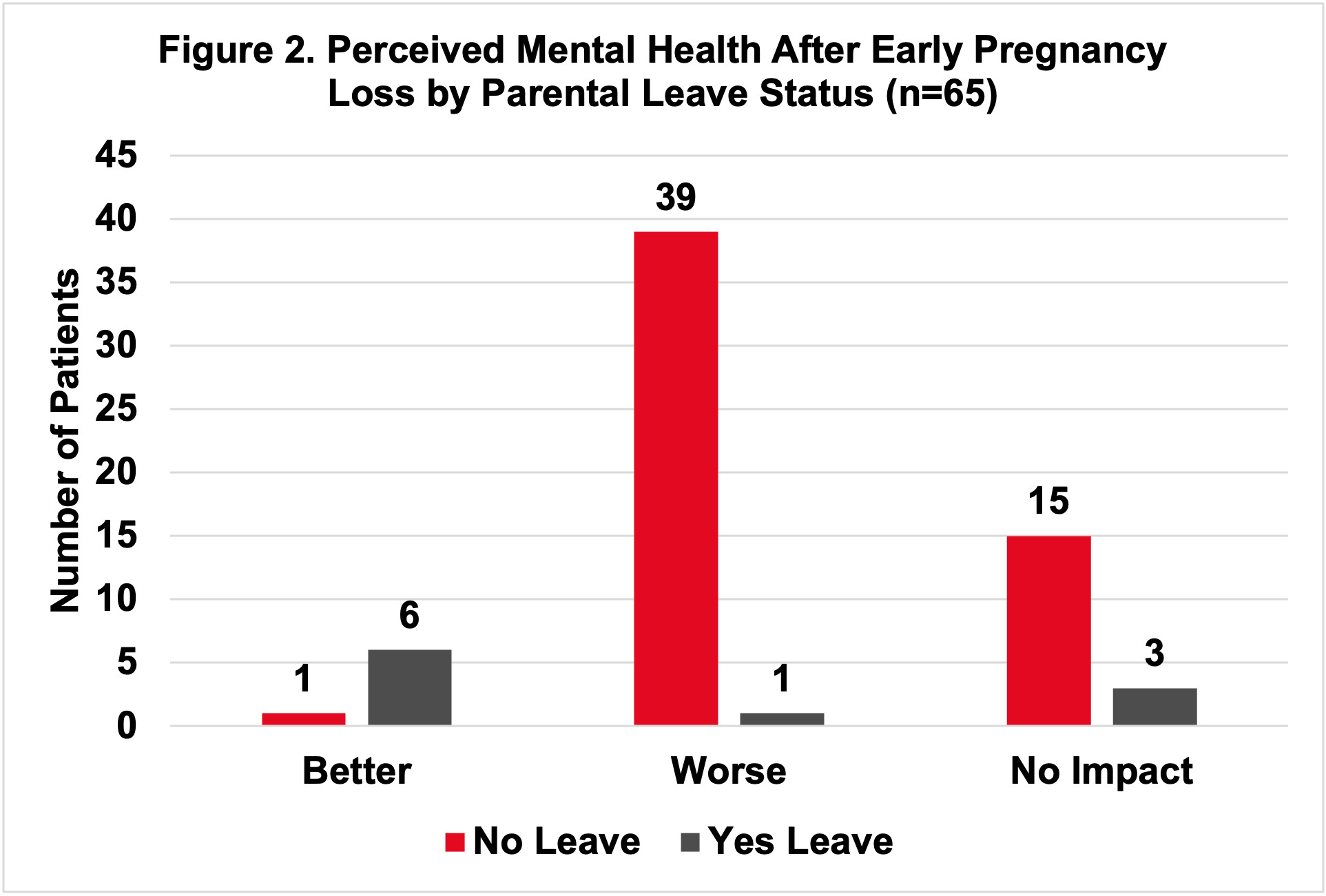

The relative risk of patients believing their mental health was better due to leave was 33.45 (CI: 4.72-236.89, p<0.001) (Figure 2).

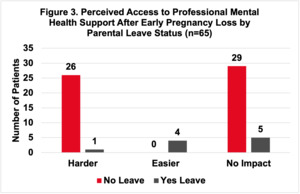

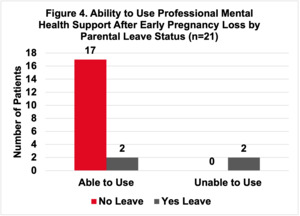

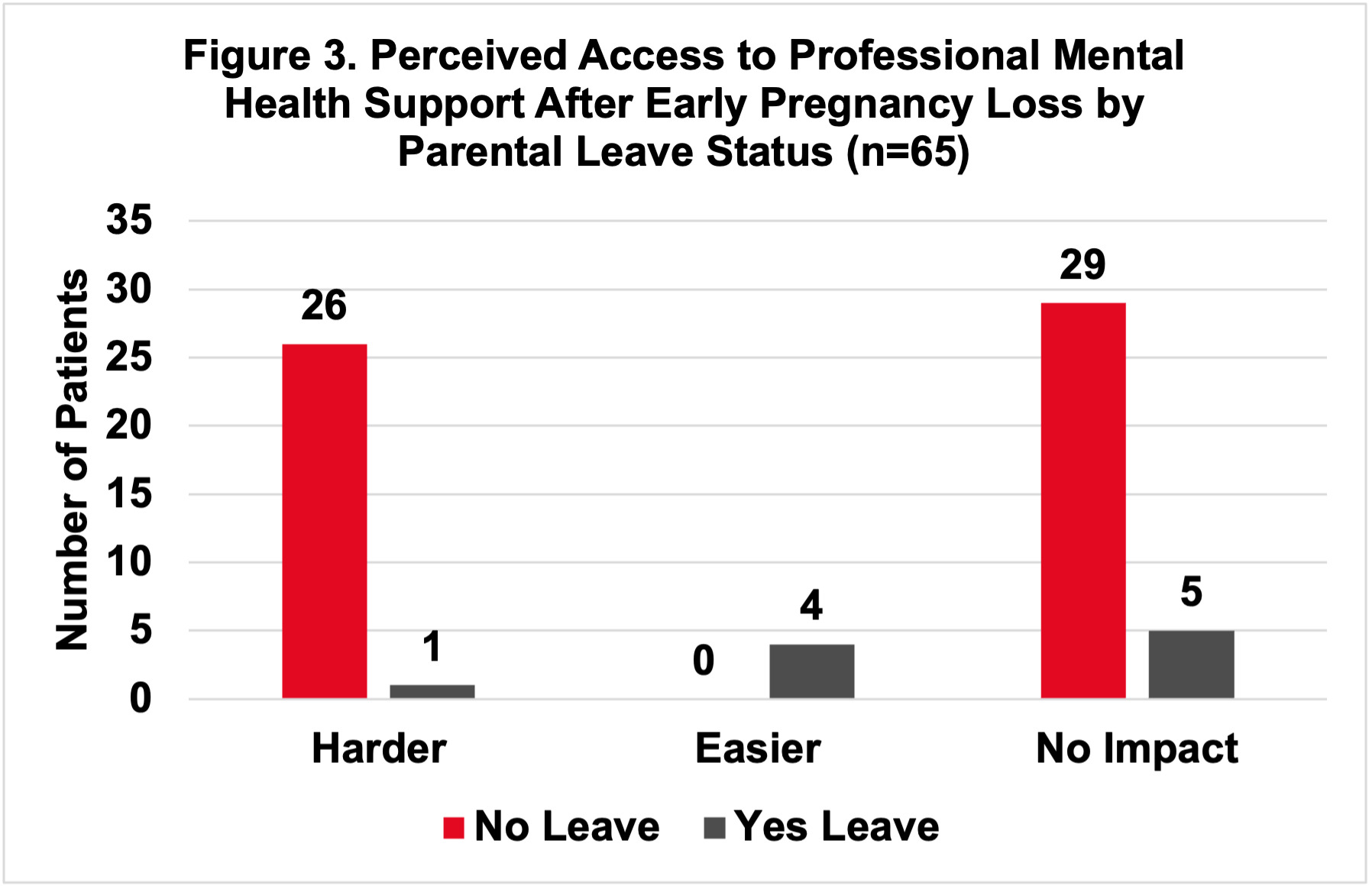

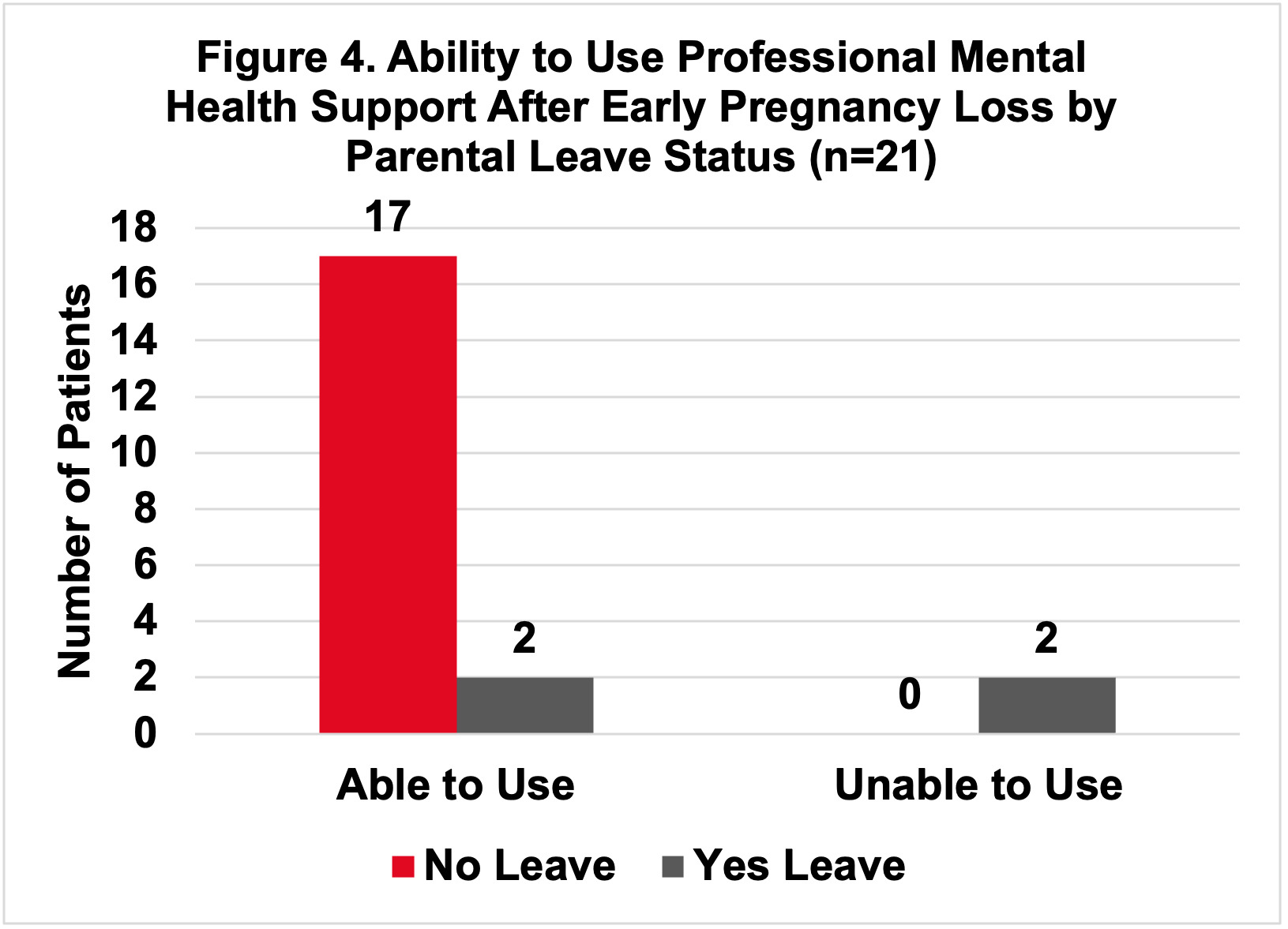

Patients that took parental leave were statistically more likely to believe they could access professional mental health support if needed (χ2[1,n=65] = 23.8815, p<0.001) (Figure 3). In practice, though, patients that took parental leave were less likely to access professional mental health support among those that did need access to support (χ2 [1,n=21] = 9.395, p<0.01) (Figure 4).

Discussion

Principal Findings

There was a significantly lower modified PRIME PHQ depression score for those that took parental leave after early pregnancy loss compared to those that did not take parental leave. These patients were also more likely to believe their mental health was better due to having this parental leave. They also were more likely to believe they could access professional mental health support, though in practice they were not.

Results

Parental leave led to fewer reported depressive symptoms compared to those that did not take parental leave after an early pregnancy loss. This is similar to findings in prior studies which found that postpartum parental leave can help reduce depressive symptoms (Kornfeind and Sipsma 2018). As such, it supports the idea that this new policy concept is indeed achieving what it was designed to do. While it may not entirely eliminate depressive symptoms, as there was a mean score of 3.5 (SD 2.12) out of 9, the mean score decrease of 1.85 means that parental leave can allow for more patients to experience a lower mental health burden. Conclusions cannot be drawn about the impact of paid vs unpaid parental leave policies in this study, as only 5 patients were in each subcategory.

Those that took parental leave also had a more positive perception of mental health. Previous research has found that a positive outlook can protect mental and physical health from the negative impact of traumatic events (Taylor et al. 2000). Early pregnancy loss is one of those traumatic events, as in the 9 months after the loss, patients experience high levels of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression (Farren, Jalmbrant, Falconieri, et al. 2020). As such, the positive mental health perception among those taking parental leave could have a protective impact as they undergo recovery.

Stigma also may be contributing to some of these findings. A prior study that interviewed patients experiencing pregnancy loss found that many of them were worried about the stigma of asking for time off and discussing pregnancy loss, and that they were unsure what policies were available to them (Gilbert et al. 2023). This was again seen in this study, as patients that were unable to take leave responded with similar concerns in the open-ended final question. One patient was unsure of what policies were available at their workplace and ended up not taking time off, despite their desire to do so. Another patient mentioned that they were frequently told that this was a normal experience, leading them to feel that their level of grief was inappropriate. As such, patients’ perceptions of whether stigma is present in their situation or not could be playing a role in their motivation to ask for leave and their mental health outcomes.

A surprising finding in this study was that patients who tried to seek out professional mental health support in the parental leave group had a harder time than those who didn’t have parental leave. The small sample size for this subgroup limits our ability to interpret why this occurred or if this finding was due to chance alone. An avenue to explore further could be other barriers to access, such as cost, appointment availability, and transportation may also be impacting access.

Clinical Implications

While parental leave for early pregnancy loss is still a newer concept, this research is timely as more companies and governments consider this policy. In 2023, California signed into law a leave policy granting California workers up to five days off after a pregnancy loss (California Government Code § 12945.6 2024). Furthermore, the United States Congress had the Support Through Loss Act proposed to provide seven paid days of leave after a pregnancy loss (Support Through Loss Act, HR 6103, 118th Congress, 1st Sess 2023). While United States employees are still able to access time off through existing federal policies, such as Family Medical Leave Act, dedicated policies for pregnancy loss will allow them to preserve the other days allotted for medical care and sick days (Kessler 2023). Other countries have already implemented varying parental leave policies, such as New Zealand, India, the United Kingdom, and Philippines (Hodson and Jerram 2023). As these and other new policies are debated and implemented in the United States, this study can begin to provide support that parental leave after early pregnancy loss is indeed beneficial.

Research Implications

Future research should work to follow patients immediately after their pregnancy loss and track mental health outcomes to reduce recall bias. A larger sample size should also be gathered, which can be done by increasing the number of sites included in the research. Further questions should be asked relating to stigma and other barriers to accessing professional mental health support.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact parental leave can have on mental health. However, its recent creation also means a smaller sample size to investigate. The survey format is also a limitation, as self-reporting can lead to recall bias or differences in understanding the questions. Its online delivery in English also limits potential respondents to only those who understand English and have internet access, limiting the generalizability. Furthermore, patients may self-select to respond if they had a more negative or more positive experience, introducing a selection bias. Finally, while some characteristics, like leave duration and annual salary, did not significantly change results when controlled for, other characteristics, like company environment and position level, may have an impact on results that should be explored further in future studies.

Conclusion

More companies should provide parental leave policies to their workers, either through a pregnancy loss policy or as a broader bereavement policy. This can help benefit their workers’ mental health, encouraging a full return to work when it is time. Governments should also continue to pass legislation expanding access to parental leave, so that other sick leave policies are left intact. Finally, physicians working with patients experiencing pregnancy loss should encourage them to inquire with their employers about leave options available to them.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Emily DeFranco for her guidance on statistical analysis methods and use of STATA.

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

Alexandra G. Kells received a stipend through the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine Women’s Health Medical Student Scholar Program to support living expenses during the research period. The program played no role in any preparation.

This research was presented as a poster at the 2023 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Districts I & V Annual Meeting in Newport, RI on October 28, 2023.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alexandra G. Kells, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 3230 Eden Ave, Cincinnati, OH, 45267. Email: graysoap@mail.uc.edu, alexgkells@gmail.com Cell Number: (859) 443-8650