Introduction

Rupture on an unscarred uterus is a very rare event, with most sources describing it on the order of 1/5700 to 1/20,000 deliveries (“ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 205: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery” 2019). The risk factors for this complication are still being described, but typically include high multiparity, use of uterotonics, advanced maternal age, macrosomia, malpresentation, placental invasion, and prolonged labor (Al-Zirqi et al. 2015; Smith, Mertz, and Merrill 2008). Typically, the standard of care for management of uterine rupture is surgical management via open laparotomy to attempt to repair the rupture or to perform a hysterectomy (Peker et al. 2020). However conservative options, such as observing a patient that is otherwise clinically stable with a uterine defect is not unreasonable given recent clinical literature evaluating similar management options after large retroperitoneal or uterine hematomas noted after vaginal delivery (Rafi and Muppala 2008, 2009). In these case series, large non-expanding hematomas are often managed with observation instead of primary repair as the risk of opening this hematoma to access the original site of bleeding could result in more complications than allowing the bleeding to resolve on its own within a confined space.

We describe a case where this concept was used to guide conservative management of a uterine rupture noted after a vaginal delivery on an unscarred uterus. In our clinical scenario, this uterine rupture, which was identified on CT, caused the development of a large non-expanding hematoma which was contained by the serosa and broad ligament. This rupture and the associated hematoma were managed conservatively. This is this first case report of a confirmed uterine rupture managed in this way as previous case series have only discussed this technique for non-expanding retroperitoneal hematomas.

Case Summary

A 39-year-old gravida 5 para 4 female with a history of pre-eclampsia in a prior pregnancies was admitted for induction of labor at 40 weeks gestation. Her prenatal course was notable only for an uncomplicated COVID infection at 36 weeks gestation. Her induction of labor was complicated by pre-eclampsia with severe features in the setting of thrombocytopenia (96 x 109 platelets/μL) and elevated serum creatinine (1.18 mg/dL), and she was administered magnesium therapy for seizure prophylaxis. The patient had a protracted labor course but had an otherwise uncomplicated spontaneous vaginal delivery 20 hours after the start of her induction.

Immediately after delivery, the patient complained of severe right lower quadrant abdominal pain which was initially described as a 9/10 intense ache which worsened with movement. She was evaluated and noted to be hemodynamically stable with a mildly distended but extremely tender right abdomen. Pain management was attempted with acetaminophen, ketorolac, and eventually oxycodone, but these medications only provided mild temporary relief, and the patient quickly reported worsening pain shortly after each administration. Her vital signs were stable, and repeat abdominal exam was notable for guarding and a positive Rovsing and Psoas sign. A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam did not reveal evidence of peritoneal bleeding, but due to pain out of proportion with an otherwise uncomplicated vaginal delivery, computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained.

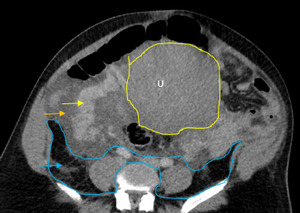

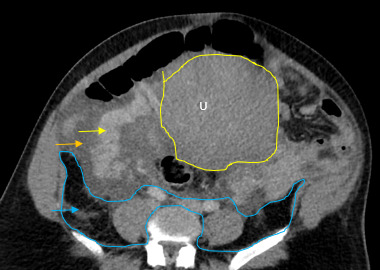

The initial impressions of the axial and coronal CT images revealed dilation of the right ovarian vein in addition to intraperitoneal fluid accumulation on the right side (Fig. 1-2). Portovenous and delayed phase images did not demonstrate contrast pooling or persistent hyperattenuation to suggest hyperacute hemorrhage (Fig. 3-4). Additionally, there was evidence of peritoneal air present between the uterine myometrium and ovarian vasculature most notable along the right aspect of the anterior inferior uterus. A contour abnormality along the right parasagittal lower uterine segment was also noted and interpreted as a uterine defect without signs of free intraperitoneal hemorrhage. In conjunction with her clinical picture, these radiologic findings raised our suspicion for a contained uterine rupture although there were no pathognomonic imaging findings to confirm an associated retroperitoneal hematoma. The patient was urgently taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy to confirm the diagnosis and to manage surgically if indicated.

There was no evidence of hemoperitoneum upon abdominal entry. There was a minor 1 cm x 1 cm superficial serosal defect noted at the right cornua, which was hemostatic and secondary to manipulation of the uterus. Most notably, a large non-expanding right-sided broad ligament hematoma measuring 15 cm x 6 cm was noted extending into the retroperitoneal space over the site of suspected uterine rupture (Fig. 5-7). The patient remained hemodynamically stable intraoperatively, and following direct observation, the hematoma was noted to be non-expanding. The uterus was taken off tension, and the decision was made to close the patient without further intervention.

Postoperatively, a multimodal pain control regimen was started, consisting of morphine, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen, which adequately controlled her pain. Patient was discharged on post-operative day 3 with minimal pain and a greatly improved abdominal exam. On post-operative day 7, the patient returned to the OBGYN Clinic for repeat evaluation, noting resolved pain and benign physical exam. She reported no other concerns throughout her postpartum period.

Discussion

Our case describes conservative management of a uterine rupture. In most cases of uterine rupture that occurs intrapartum, the diagnosis is made clinically with evidence from the physical exam in addition to changes in fetal heart rate tracing. However, in our case, her initial symptoms occurred immediately postpartum, and, imaging was necessary to make an informed decision for care. Therefore, expert consultation and collaboration with a multi-disciplinary team is critical to ensure proper and timely diagnosis.

Uterine rupture was highly suspected even prior to the exploratory laparotomy due to the presence of air between the uterine myometrium and the ovarian vessels. Figures 1-4 describe CT findings consistent with uterine rupture. This is the first case report of a uterine rupture being managed conservatively similarly to previously described management options for contained uterine hematomas.

While the CT raised our suspicion for uterine rupture preoperatively, it did not predict for the size and extent of the broad ligament hematoma that we observed intraoperatively. It was appropriate to perform an exploratory laparotomy as most uterine ruptures require surgical management. The decision to manage conservatively rested on the non-expanding nature of the hematoma, an intact broad ligament, and the patient’s hemodynamic stability. As these safety checks were passed, we decided to conservatively manage the defect and to avoid the more morbid hysterectomy as well as its potential complications.

In reviewing the current literature around uterine ruptures, several considerations are worth discussing. Our patient had several risk factors for uterine rupture including multiparity, use of uterotonics and cervical ripening agents, advanced maternal age, macrosomia, and obstructed labor. Peker et al. published a retrospective review in 2020 of 67 unscarred uterine ruptures which occurred at a Turkish tertiary care center over 12 years. This study suggested that in populations with one or more of these risk factors present, the incidence of uterine rupture after uncomplicated vaginal delivery may rise to a number closer to 1 out of 2770 women (Peker et al. 2020). It is notable that our patient had very similar but slightly lesser pain after her previous pregnancy that resolved spontaneously over 3-6 months and was not evaluated by postpartum imaging. It is possible that this uterine defect was present in the last pregnancy which may have caused a similar but perhaps smaller hematoma that resolved spontaneously. Puerperal and retroperitoneal hematomas are rare occurrences in the obstetrical literature, and only a handful of case reports have been published to describe management options (Rafi and Muppala 2008, 2009; Rafi and Khalil 2018; Kim et al. 2011; Alturki, Ponette, and Boucher 2018). In the past, these hematomas were thought to be exclusively iatrogenic and specifically noted after caesarean section. However, Rafi and colleagues describe a rare case of a massive hematoma following an uncomplicated spontaneous vaginal delivery that was managed conservatively. Our case is unique, however, as none of these described hematomas were confirmed to be secondary to a uterine defect.

While this is a unique management option in a very specific situation, it would not be appropriate if the patient had been hemodynamically unstable; surgical repair would have been warranted. Most ruptures occur at the isthmic region of the uterus, which is what we noted here as well. Fundal ruptures are typically more complicated and are associated with worse outcomes. While data on repeat pregnancies after unscarred uterine rupture is limited, the overall risk of recurrent rupture is somewhere between 22-100% based on a handful of case series (Gupta et al. 2016; Dow et al. 2009). Similarly, while there is no consensus on timing of repeated delivery, many physicians recommend a scheduled cesarean section at 36-37 weeks with an isthmic rupture and recommend choosing a date closer to 32-33 weeks for a higher risk fundal rupture (Landon and Grobman 2016). Patients, such as our own, should also be counseled appropriately regarding short interval pregnancy and future risk of rupture recurrence. In this case, our patient was not planning any future pregnancies.

In conclusion, rupture of an unscarred uterus is an extremely rare occurrence but can have catastrophic maternal and fetal outcomes. Once the diagnosis is made, the standard management of uterine rupture is emergent surgical management in the setting of hemodynamic instability and possible fetal distress during labor. Conservative management may be a reasonable option in select patients that are hemodynamically stable with a rupture that is contained and non-expanding. These ruptures likely have potential to self-resolve with supportive care, but proper counseling should be provided for future pregnancies and patients must be given clear recommendations on mode as well as timing of delivery. Our report, albeit specific to our patient, can be utilized as a guide for future providers in considering other alternatives to manage uterine rupture.

_and_delayed_phase_(ri.png)

_and_delayed_phase_(ri.png)